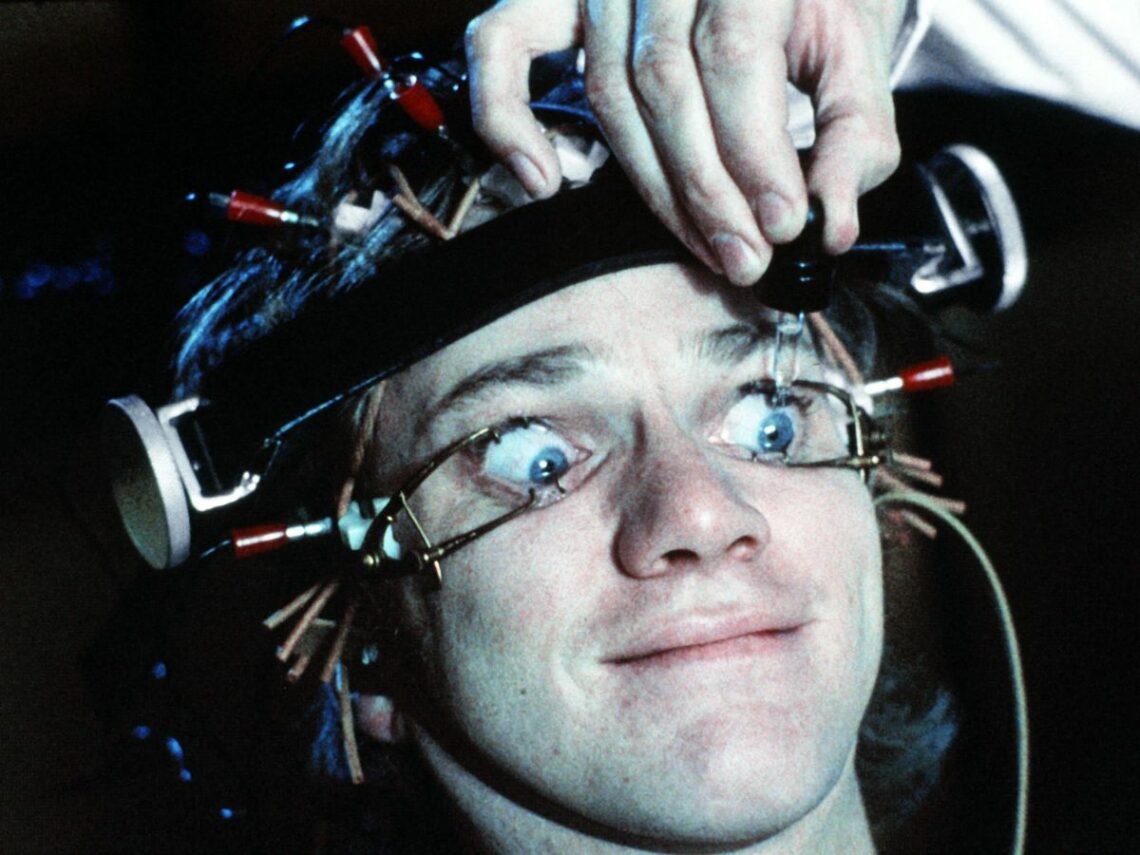

Netflix may well have some high-class original content on its shelves, but it also contains some of the greatest movies ever introduced to cinema. A Clockwork Orange, the ultra-violent masterpiece by Stanley Kubrick, can undoubtedly be considered one of those movies. However, the director wasn’t always a fan of the production.

It’s not exactly rocket science to figure out why A Clockwork Orange was banned in British cinemas. Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ iconic novel is still counted among the most unique film adaptations of all time, almost fifty years after its release. Kubrick applied his fiercely original vision to Burgess’s ideas. The result was a work of unparalleled aesthetic quality blighted by the searing violence and gross representations of a dystopian world that didn’t feel so far away. The visceral nature of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange is an achievement of the highest order but one that was always guaranteed to grab the attention of conservative censorship.

The real curiosity occurs when it becomes apparent that Kubrick himself eventually recommended the film be removed from British cinemas. By doing so, he enacted one of the most successful censorship campaigns in pop culture and, with time, made A Clockwork Orange an unrivalled cult classic. Relegated to the seedy backrooms of video stores and the teenage witching hour viewings, the film took on a brand new guise as the intellectual’s favourite gorefest. But why did Kubrick see fit to have the film banned?

Let us be clear, though it may be considered a masterpiece today, regarded as one of the iconic director’s finest films, A Clockwork Orange was not well received by audiences or critics. Audiences were left aghast by the flagrant adoration for violence and chaos that seemed to permeate the film, most prominently seen in our anti-hero Alex DeLarge, a confessed gang leader, bruiser, murderer and rapist or as he neatly puts it, “a bit of the ultra-violence.” Critics, too, felt that Kubrick had gone one step too far and rather than make a point about the crumbling society around, he was asking those watching the film to pick up a few rocks and start hurling them wherever they saw fit.

This was the concern that underpinned all of the right-wing rhetoric that was surrounding the film. Kubrick, in their eyes, had provided a blueprint for copycat violence to erupt across Britain. Forgetting the fact that Ben Hur saw zero copycat chariot races take place, their concerns feel rooted in fear if not intelligence. Newspapers were routinely lambasting the film as they jumped at the chance to stoke some fires. Publications claimed that the film was a “ticking time bomb” just waiting to turn London’s streets into a dystopian nightmare of ghoulish gangs and frightening violence.

It was a struggle for Kubrick. The director had set up his home in Britain, and the constant abuse from the tabloid press — a noted evil in the world of mass media in Blighty — must have weighed heavily on his mind. The papers were full of escalating violent outbreaks attributed to A Clockwork Orange, and the visceral images of real-life pain may have pushed Kubrick into his next action.

By 1974, Kubrick teamed up with the film’s distributor, Warner Bros, to have the film withdrawn from circulation. The censorship was swift and wide-reaching. The conditions saw the film be played under no circumstances for an audience or risk facing the penalty. It put most cinemas off trying to breach the rules. London’s Scala cinema showed the film in 1992 only to have its doors shut permanently for breaking the rules.

“Stanley was very insulted by the reaction, and hurt,” David Hughes quotes his widow Christiane as saying in his book The Complete Kubrick. It appeared that, unlike many of his contemporaries who thrived in the unknown, Kubrick didn’t want to be misrepresented or misunderstood. His real annoyance seemed to come from the overreaction to something he saw as prevalent among every art form. “There has always been violence in art,” he told journalist Michel Ciment before the film’s release. “There is violence in the Bible, violence in Homer, violence in Shakespeare, and many psychiatrists believe that it serves as a catharsis rather than a model.”

The director followed that up by saying, “the people who commit violent crime are not ordinary people who are transformed into vicious thugs by the wrong diet of films or TV. Rather, it is a fact that violent crime is invariably committed by people with a long record of anti-social behaviour or by the unexpected blossoming of a psychopath who is described afterwards as having been ‘…such a nice, quiet boy.’”

Kubrick completed the damnation of such a notion by saying, “immensely complicated social, economic and psychological forces are involved,” and “the simplistic notion that films and TV can transform an otherwise innocent and good person into a criminal has strong overtones of the Salem witch trials.”

We’re not sure how easily Kubrick should have given in to public pressure surrounding his art. Whether he felt strongly about the censorship or was just in the process of seeking an easy life, the fact is that Kubrick presided over one of the most robust censorships of art Britain has ever witnessed, the film staying off cinema lists until the year 2000 when it was re-released.

Censorship or no censorship, one thing can be guaranteed — banning a film never stops people from watching it. Watch A Clockwork Orange on Netflix now.