While Netflix may now be firmly implanted within the filmmaking structure, having even taken home some Academy Awards in the process, their shelves aren’t only filled with original material. They also have a fine selection of classic movies, and, in Netflix Flashback, we pick out a gem of the past to showcase once more. This week it’s A Clockwork Orange by Stanley Kubrick.

Shunned upon its release for its brutal and uncensored depictions of sex and violence, A Clockwork Orange was a difficult piece of art to comprehend for general audiences when Stanley Kubrick released the film in 1971. Undecided as to whether the film should be praised for its poetic, if morbid, representation of contemporary society or whether it should be pulled from cinemas for its worrying suggestion of personal agency, Kubrick’s film remains an enigmatic piece of filmmaking.

A complex essay on the manipulation of human consciousness, Kubrick’s film, adapted from the 1962 novel of the same name by Anthony Burgess, is a cauldron of different concepts that entwine to draw up a terrifying vision of a future reality. Depicting a strange reality, A Clockwork Orange is set in a dismal English city caught between the past and future where gangs roam the streets, and the higher classes live far away.

Stalking the streets and terrorising just about anyone who crosses their path, the film follows Alex (Malcolm McDowell), a vicious thug and lover of Beethoven, and his ‘droogs’, a gang of white-clad youths with black bowler hats and a thirst for “a bit of the old ultraviolence”. Such reaches an alarming pinnacle when the group invades the house of Mr and Mrs Alexander, a wealthy couple of artistic tastes who live on the outskirts of the city.

Breaking their way into the house, Alex attacks the woman with a giant phallic sculpture. She retaliates with a bust of Beethoven, a literal representation of the psychological battle between one’s own animalistic I.D vs. the social and civilised Superego. Showing Alex’s physical battle with his mind and body, between socially-taught norms and the sexual desires of his own body, unfortunately, his desires prevail; a metaphor for the way Alex lives his selfish life, putting himself before the progress of society.

The counterpart to such sexual desire is the closely linked theme of carnal violence that pervades the film. Not only are the gang disturbing sex pests but they’re violent thugs too. This idea is embodied in the theatre scene at the start of the film when Alex and his droogs take on a rival gang in a shelled-out theatre. Theatrical and disturbingly entertaining, the whole scene is made to feel constructed and rehearsed as gang members fly across the screen, through windows and over heads with no blood or graphic detail.

A prophetic message considering the 1970s context, the scene relates to how modern audiences view violence, with the theatre brawl drawing comparisons to the violence of contemporary entertainment that sees enjoyable brutality without the long-term consequences for its characters. Taking place in the very space of theatrical performance, the scene is an active metaphor for the battle between art and entertainment. As Alex Baxter, the author of Stanley Kubrick: A Biography notes, the scene is more of an “intellectual argument, rather than a sadistic spectacle”.

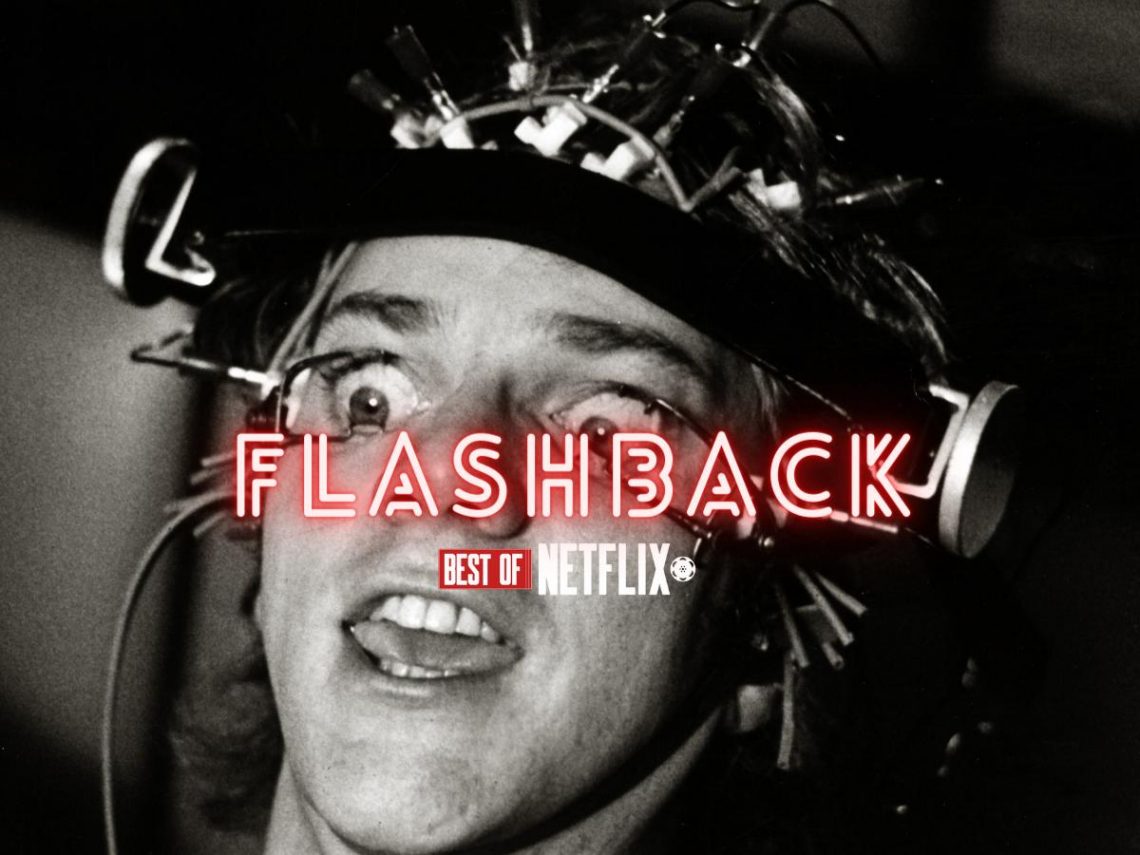

The effort to suppress such sexual and violent acts is certainly enacted by the harsh higher-powers of the film, too, with their newly developed Ludovico treatment essentially built to eradicate all ill-thoughts of violence, strip free and force the individual into adopting the ideology of a perfected society. This technique works for a while, too as Alex is freed into the real world, only to feel sick when he considers going back to his violent and sexual ways, even if his true identity eventually seeps out. Whilst a government can try to enact their own vision of uniformed identity they are ignorant to the fact that such sexual and violent thoughts are such that are deep-rooted in an individual’s DNA.

Even those you assume to be ‘civilised’ in the film such as the probation officer, Deltoid, possess a vivid sense of sexuality, showing that no matter your position, such carnal thoughts are innate. Letting people enact their free will however they choose keeps them, essentially, people and prevents them from going mad. As Stanley Kubrick told film critic Michel Ciment, Do we lose our humanity if we are deprived of the choice between good and evil? Do we become, as the title suggests, ‘A Clockwork Orange’?”.

The primal instincts of humanity will always prevail over the potential of ‘control’.