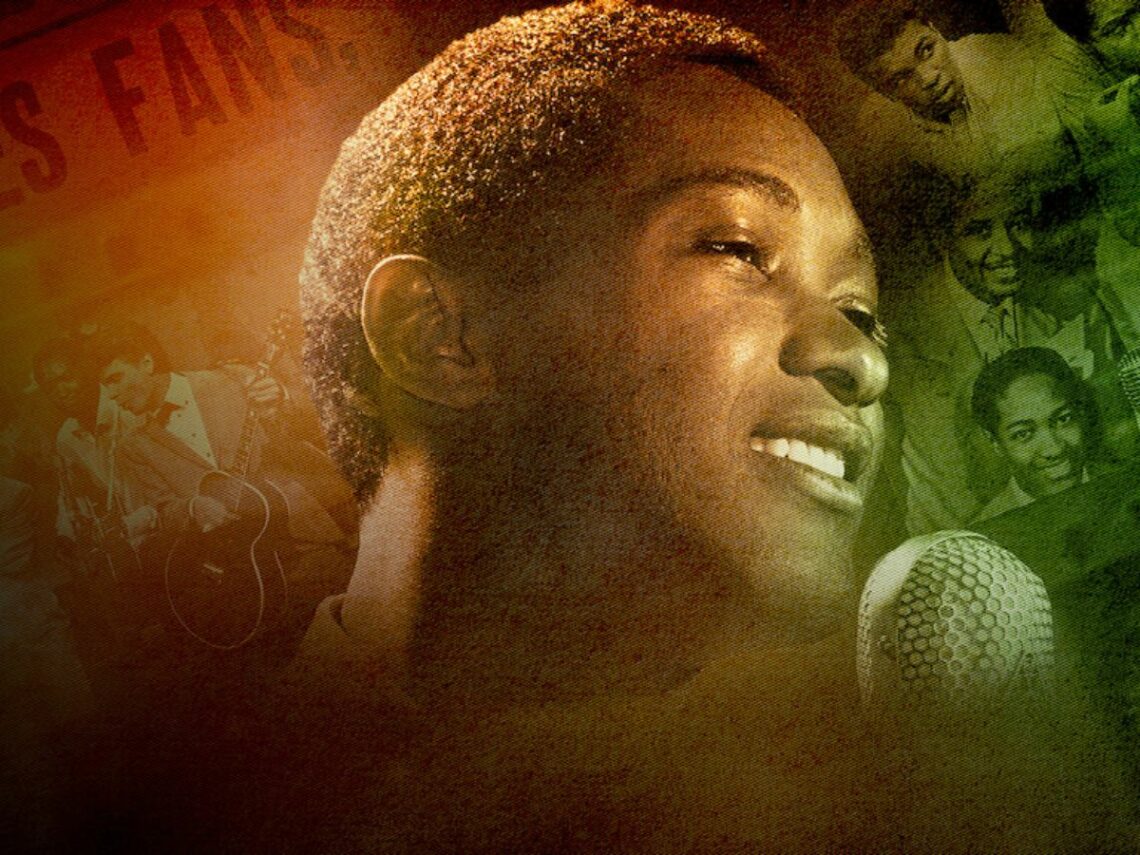

Who killed Sam Cooke, and why?

The impact of Sam Cooke’s all-too-brief life on the history of music can’t be overstated. And since 2019, it’s been celebrated on Netflix in the documentary The Two Killings of Sam Cooke. Aside from having the smoothest voice in soul, the singer arguably became the first star-turned-mogul in the business by setting up his own record label and one of the songs that would come to define the 1960s.

Cooke’s civil rights anthem ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’, released posthumously 11 days after he died, was at once a cry of desperation and a clarion call of hope. It signified the limbo of an African-American community still in the process of extricating itself from profound institutional and social oppression. Cooke agreed with his musical collaborator Bobby Womack when he told him the song “sounded like death”. After recording it, he only sang it once in public during his lifetime, in a recording of The Tonight Show which is now lost.

Just ten months after that performance, the song would become forever intertwined with death under the most unexpected of circumstances, as Cooke lost his life at the age of just 33. And the mystery continues to swirl around the specific circumstances of this tragic event even today, perpetuating conspiracy theories which have been put forward from the moment it happened.

What we know for certain is that a young woman called the police via a phone booth close to the Hacienda Motel in Los Angeles in the early hours of December 11th, 1964. She told the police, “I was kidnapped.” A few minutes later, Cooke was dead.

So, what happened at the motel?

The young woman on the phone was Elisa Boyer, who’d met Cooke earlier in the evening at Martoni’s Restaurant in Hollywood. Cooke had had dinner there with his label’s recording engineer Al Schmitt, and Schmitt’s then-wife Joan Dew. During the meal, Dew recalls, Cooke took out a large wad of cash and put it on the table. “Don’t be flashing that money here,” Schmitt told him, “Put it back in your pocket.”

As the couple said their goodbyes, Cooke went up to the bar, where Boyer happened to be sitting, and the two began chatting. After drinking late into the night, Cooke insisted on driving Boyer to a motel. He did so against her will, according to her testimony on the witness stand, as she told him repeatedly, “Please take me home.”

The two ended up at the Hacienda, where Cooke allegedly attempted to rape Boyer before she fled the scene while he was using the bathroom, accidentally taking some of his clothes with her. That’s where Boyer’s part of the story ends.

Who shot Cooke, then?

Cooke went looking for her, and apparently pounded on the door of the motel manager’s office, thinking he’d find Boyer hiding in there. Instead, he found the Hacienda’s manager, Bertha Franklin. “He grabbed both of my arms,” Franklin told the court presiding over the ruling on Cooke’s death, “and started twisting ’em and asked me where was the girl.”

In response, Franklin said, she was “fighting, scratching, biting and everything” she could to get a near-naked Cooke off her. “Finally I got up and grabbed a pistol.” She aimed and shot three times, hitting the singer once in the heart, which proved enough to kill him. He lunged at her, before slumping to the floor when she hit him over the head with a broomstick.

Certain inconsistencies remain in this version of events. For example, Dew has claimed the wad of cash she saw Cooke place on the table at Martoni’s contained around $5000, but the police only found $108 in his wallet the following day. In the documentary, Boyer is painted as a “Hollywood hooker” who conspired to rob the musician with her pimp.

More broadly, those who knew Cooke point the finger at the police or the FBI, claiming the extent of his head and neck injuries didn’t match Franklin’s description of events. Many believe there was a political motive behind the killing, stemming from Cooke’s prominent position in the struggle for black rights. Others attempt to argue that the manager of the singer’s label Allen Klein might have had something to do with it for financial reasons.

But Franklin and Boyer’s testimonies remain the main body of evidence we have to go on. The other theories are simply conjecture, and might continue to be for all time. The tragedy of what occurred is beyond question, leaving music without a figure who’d led the black power movement alongside the likes of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. Others would come along to fill that void, but Cooke’s towering legacy as one of the progenitors of soul music and African-American political consciousness continues to inspire new generations of musicians today.