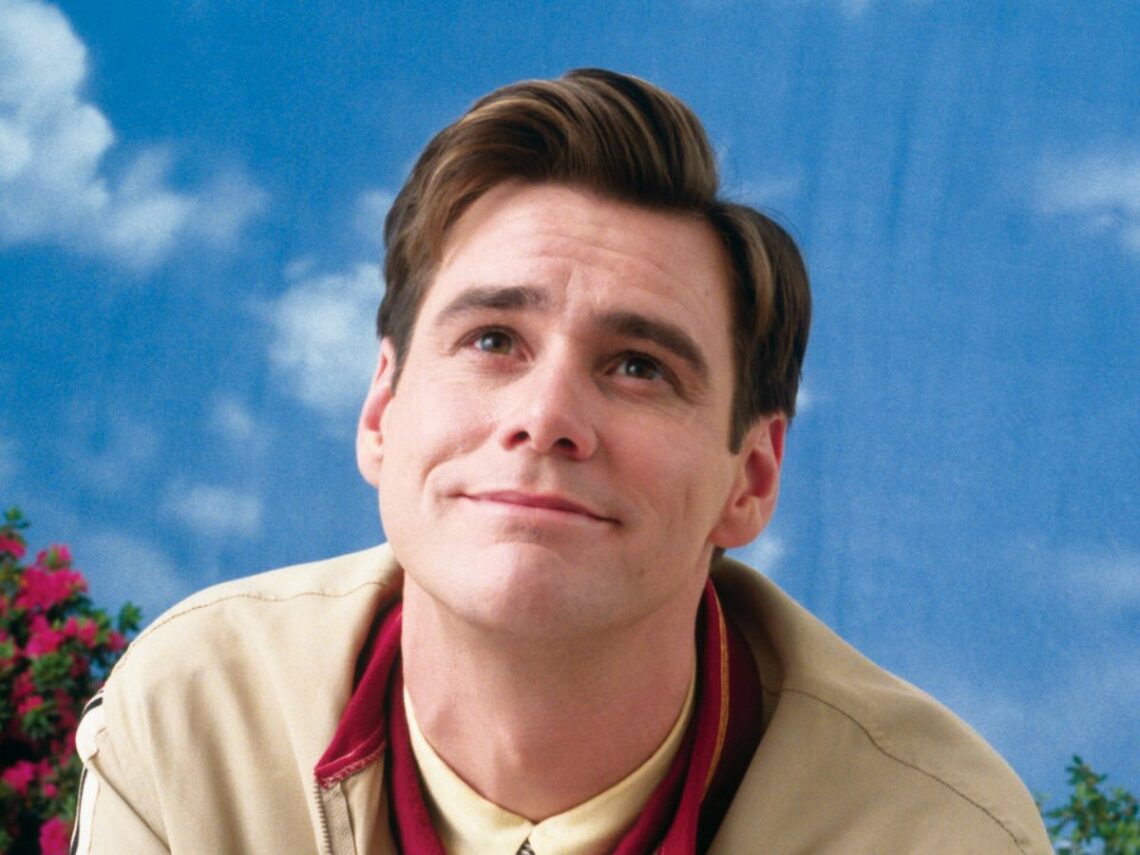

Sure, the cinema of the 1990s and early ’00s may have been richer in teen comedies and light-hearted romps than it was in dystopian dramas, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t equally riddled with a sense of disillusionment. Netflix has two movies that effortlessly captured these feelings, and Jim Carrey starred in both of them.

The Truman Show (1998) and Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind (2004). Despite their tonal and stylistic difference, each of these films centres on a character attempting to find meaning in a world out of their control; all feature individuals attempting to come to terms with the unbearable monotony of freedom, and all lead us to question how we should live in a world where everything is handed to us.

Distrust of power is an essential feature of 1998’s The Truman Show starring Jim Carrey. The film tells the story of a man named Truman Burbank, who has been born and raised – unbeknownst to him – in a gigantic television studio designed to resemble the real world. Truman grows up completely unaware that his life and his entire reality are a fabrication; that is, until light falls from the sky, the first of many ruptures to this all-consuming illusion. Indeed, everything in Burbank’s life gradually turns out to be a feature of the TV show that is his life. Teachers, friends, strangers: even the words of his family members have been scripted. Conversations are never just conversations but opportunities for the TV network to sell a certain product to the viewing public or else to keep Burbank locked inside his fake reality.

The more Truman questions the nature of his reality, the more he realises just how ridiculous it is, setting him on a spiral towards madness. “Why don’t you let me fix you some of this new Moccocoa drink,” says Truman’s wife, Meryl, turning to face the studio cameras. “What the hell are you talking about?” Truman replies as his wife’s pearly smile begins to wither. “What the hell does this have to do with anything!” he yells, echoing a discontent not only with the consumer-addled modern world but with the artificiality and emptiness it engenders.

It’s no accident that Truman’s home town has been designed to resemble a 1950s suburban idyll. White picket fences, homemade apple pies, besuited businessmen with wide smiles: the town of Seaside, Florida, is riddled with the iconography of the American dream. Truman’s gradual realisation that this iconography has, in fact, been put in place by a set dresser reflects growing disillusionment with America’s founding myth and a disdain for those who continued to espouse its benefits. The Truman Show shows us how the way we perceive reality is governed not by our own will but by the dominant ideology of the time. Truman’s world is much like our own in that the messaging of that ideology is embedded in every corner of society. From education to the media and government, everything ends up being a mouthpiece for the system.

According to a study conducted by John Zogby, the Millenium coincided with a redefinition of the American Dream. He discovered that while one-third of Americans still believe the American Dream meant being financially secure and having access to consumer products, an equal proportion rejected the ideal’s emphasis on materialism.

These “Secular Spiritualists” (descendants of the counterculture movement) believed that life was about being genuine, about achieving a legacy larger than one’s self.” And yet, they continued to submit to consumer capitalism. Why? Well according to Michel Gondry, the director of 2004’s Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind, because submitting to the dominant ideology is so damn appealing. Gondry’s film is set in a world in which individuals are able to have their memories removed for a fixed price. It is a world in which people are so familiar with having their emotions manipulated by third parties that they happily give up their memories to avoid pain, grief and heartache.

Rewatching Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind, I’m reminded of Slavoj Žižek’s observation that our familiarity with being given a product without that product’s harmful aspects is beginning to affect our understanding of romance. In the same way, we want sugar without calories and beer without alcohol; we also want intimacy without the fatal attachment that follows falling in love. This is precisely the mistake Joel and Clementine make, Gondry argues.

The pair are flawed individuals who lack objective judgment because they have been taught to live according to their own individualistic desires. Their decision to erase one another from their lives is determinantal because it cuts them off from suffering. In the same way that Phil and Truman’s lives are empty because they are devoid of pain, the world of ESSM is nightmarish precisely because everything is so readily available. By the end of the film, however, the director has proposed that the very suffering these characters have been seeking to avoid is what makes their love worthwhile and meaningful.

The Truman Show, and Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind both betray a deep fear about our relationship with society at large. They each paint a picture of a world entirely like our own: worlds in which people rarely want or need anything. We don’t need to hunt for food. Nor are we in danger of having our village burnt to the ground by some marauding raiding party. Each of these films seems to suggest that what we should fear is the very comfort we have dedicated thousands of years securing. After all, what is life without a little rain?

Watch The Truman Show and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind on Netflix now.